Evermore Park is an interactive themed entertainment experience located outside of Salt Lake City, Utah. Ken Bretschneider, who earned his fortune in the early 2000s in a digital security company and who co-founded the virtual reality entertainment company The Void, created Evermore Park, LLC alongside former Disney Imagineer Josh Shipley. Evermore has been described as a “fantasy European hamlet of imagination” and “an experience park where guests of all ages can escape to a new realm” ( What Is Evermore | Evermore.Com, n.d.). Evermore has historically been open three evenings a week during its two-to-three-month seasonal events, and visitors can interact with costumed residents of the town who are responsible for improvising their way through a loosely constructed overarching narrative that takes many weekends to unfurl. Evermore Park is a storytelling platform that simultaneously engages all four of Steve Dixon’s four levels of interactivity: navigation, participation, conversation, and collaboration. (Dixon, 2007, p. 563). Guests can navigate the park and watch scenes play out before them, participate in quests by interacting with the characters, have in-depth conversations with actors and other visitors to uncover the story, and even become collaborators who shape the narrative by influencing how events unfold and how characters develop.

Although most of the plot beats are pre-determined by a creative writing staff, the park’s destiny is not fixed. Visitors to the park can actively engage in shaping not only elements of the story but also the dynamics between characters, the outcomes of events, and can even choose to become characters themselves by dressing in costume and adopting in-park personas. Alternatively, visitors can (and often do) choose a more passive experience by electing to stand back and watch. It can be a challenge to describe Evermore Park. For example, YouTuber Ginny Di opens her overview video called “Evermore Park is D&D in Real Life” by explaining that she didn’t know what to expect when she visited with her friends, because Google Map’s search listing described it as a “theme park” while the Evermore website used the phrases “experience park” and “a world of play.” “Was it going to be like a Renaissance Festival? Was it going to be like a LARP? Was it going to be like Westworld without robots?” she wondered. The answer, it seems, is a little bit of everything because encourages engagement across the spectrum of interactivity. How visitors interpret it often involves making references to related media and entertainment that occupy each of Dixon’s levels of interactivity. Interviews conducted at the park during two visits in 2019 most often revolved around a spectrum of pleasures of agency (Murray, 1997, p. 128) supported by design elements at Evermore that promote immersion and interactivity. In the same way that videogames negotiate the illusion that balances agency and structure (Charles, 2009; Stang, 2019), Evermore attempts to appeal to a broad audience from casual observers to dedicated participants who learn to interact with the park through designed structures and media referents.

This study of Evermore Park—close-reading/playing informed by participant observation and interviews— follows the methodological examples provided in entertainment and media tourism of Hobbiton (Peaslee, 2010; Singh & Best, 2004), Harry Potter tours in London (Larsen, 2015; Lee, 2012), and The Wizarding World of Harry Potter at Universal Studios (Gilbert, 2015; Waysdorf & Reijnders, 2018). At their core, these studies combine first-hand accounts from their authors (who are well-prepared to dissect the place) with interviews of visitors who expand the interpretive view. This article is based on four trips to Evermore Park during two different seasons in which my colleague Dr. Stephanie Williams-Turkowski and I participated in the experience, conducted interviews with attendees on-site, and examined online fan discussion to understand how the park is “played” by its audience. Because themed entertainment experiences are complex, no single methodology can capture the milieu of the place. This work is equal parts auto-ethnography, participant observation, participant interviews, close reading/playing, and design analysis. Evermore Park is continually evolving, and this work captures the state it was in from the opening season in summer 2018 through the end of its winter season in early 2020. The park was in-between seasons when the COVD-19 pandemic paused its reopening and, when it resumed for its summer 2020 season Pyrra, a number of structural changes were implemented that are different from those described here. More recently, Evermore Park LLC released a statement explaining that even its summer 2021 seasonal operating procedures were no longer tenable and will need to undergo major changes to the interactive theatrical components. I will briefly address these differences at the conclusion, but they invite follow-up study. The goal is to paint a picture of what Evermore Park was during its “initial” run, how it was experienced, and how it was perceived.

When Evermore Park opened in 2018, the company assumed that its visitors would understand how to navigate an immersive theater presentation that asked them to engage with the actors to uncover its stories. During the seven seasons the park has operated, however, its designers have adapted to different audience expectations by creating structures for play such as quests and treasure hunts. Because Evermore Park is an entertainment space that blends theater and play, this research builds off of the example set by Rose Biggin in Immersive Theater and Audience Experience which examined the popular “immersive” performances by Punchdrunk, the company whose production Sleep No More gained popular global appeal. Biggin also drew on Dixon’s levels of interactivities and her work theorized immersion and interactivity as related to the history of theater, play, and games. Her subject of study prioritizes the immersive experience in which “participants are asked to lose themselves in the drama as it progresses and makers work towards the aim of keeping illusion to a maximum” over interactive experiences in which “participants are asked to bring their own experience and understanding to bear on the drama as it progresses and illusion is kept to a minimum” (O’Grady, 2011, pp. 168–172, cited in Biggin). As a subject of study, Evermore Park offers a new perspective on the topic by providing a concrete example of how a company can operationalize the game-like potentials of immersive theater that Biggin alluded to in her later chapters, and that Rosemary Klich describes in her comparative media studies analysis of Punchdrunk and videogame interactivity (Klich, 2016).

Of particular utility here is how Biggin examined the themes that emerge when audiences are asked to describe an experience like Sleep No More. Reactions from participants (and, in particular, fans of the form) “can be used to build a vocabulary of what is valued in immersive experience, with consequences for theorising the value and effects of immersive theatre” (Biggin, 2017, p. 97). The language used by our interviewees and discussion about Evermore Park demonstrate how parkgoers find enjoyment (or do not) at each of Dixon’s levels of interactivity. Wandering the grounds and listening in on conversations is as viable a mode of interaction as adopting an in-park persona and befriending the characters. Because Evermore Park is new to both its audience and its operators, the illusion is managed by all involved. Not only does participation in an immersive storytelling world require an invitation and structure but, as Jonas Linderoth (2012) observes, it also takes sustained work by even the most motivated participants. These visitors are willing to engage in spite of the shortcomings of the system. Inside of the park, visitors can choose to engage at any level, though it is often the park’s dedicated fans who develop relationships with Evermore’s characters that enable deep collaborative labor. Outside of the park, Evermore relies on fans whose labor, as Carissa-Ann Baker describes, is used to “interpret both the space [of the park] and the practices [of fandom]” by documenting events, posting guides, and promoting this unique experience (Baker, 2016, p. 22). This magic requires work.

The journal of our experiences at Evermore Park that follows alludes to the messiness of categorizing it. Though it has no rides, it’s often discussed as a theme park because of its ambitious scale, fantastic architecture, and narrative environment. It’s like a Renaissance fair with its mashup of genre fictions, British Isle character accents, and archery contests, yet it has a persistent story that binds these elements together. It’s like a live-action role-playing event that takes place in front of an audience. It’s like a game because newcomers are encouraged to go on quests, yet the only reward is more knowledge. It’s like visiting Star Wars Galaxy’s Edge at Disneyland or Hogsmeade at Universal Studios, except that visitors are encouraged to talk with the performers and direct the action. And because visitors to Evermore Park are able to choose their level of engagement, experiences can be plotted on a wide spectrum. It’s possible to visit and never directly speak with one of the many characters who populate the town, opting instead to be a passive observer. At the other end of the spectrum, it is also possible to become steeped in the lore and wear an elaborate costume that supports a character with an imagined backstory while deeply engaging with other Everfolk. By examining how Evermore Park’s amalgamation of media—theme park, immersive and interactive theater, games, and play—is structured and interpreted, we can understand the unique experience it strives to create.

Introducing Evermore Park

The grounds of Evermore Park (called the town of Evermore) are modeled as a small European village in an architectural style commonly seen in the fantasy genre. The Evermore narrative is set during the 19th century, which means that when attendees cross the threshold into the park they are “coming through a portal” and stepping back in time. Activities in Evermore Park take place in a mix of indoor and outdoor spaces. The Crooked Lantern tavern, Hobbit-like home of the Burrows, the mausoleum, catacombs, and the Glass House (host to a bird and reptile show) draw visitors inside while outside hubs such as the town square, courtyard in front of the statue of St. Michael, faerie gardens, the paths around the crypts, the Fallen Alter Ruins, and the various canvas tents along the sidewalk that circles the town serve as public gathering spaces. Though the park shares common elements with something like a Renaissance Festival—a mashup of fantasy tropes in a historical setting—Evermore Park is architecturally consistent and plausible. The town of Evermore is populated by characters who are either residents or visitors who have come through a special portal that opens each season to new realms. Residents include the mayor and her staff, the postman, the tavern keeper and his employees, the acting troupe, the musician dwarves Lanny and Turno, and members of the various “guilds” that call Evermore home. Transient visitors from other realms may eventually come to reside permanently as the story dictates. All of Evermore’s inhabitants (“Everfolk”) are involved in a narrative that unfolds over the course of the 8–10-week season.

Each narrative season at Evermore Park begins with the same event: the opening of a portal located in the center of town. In the backstory, the village of Evermore was founded when this portal opened from another realm centuries ago and the first settlers (who we would think of as humans) came through. Not long after, the portal closed and sealed the other realms away. It remained sealed until two years ago (mid 19th century in the fiction) when a powerful witch named Wen Weaver and a scientist-inventor named James Wikam figured out a way to re-open the portal in order to explore what was within. All was well for a short while (the Mythos 2018 season) until the portal to the realm of Lore opened and various evils poured through. This inaugurated Evermore Park’s second season and was followed in the winter by Aurora and again in the summer by the re-opening of Mythos. Some actors have played the same role from season to season while others have inhabited new characters as dictated by the backstage production group who crafts the story and directs the show. Supported by the costumers, set designers, makeup and special effects artists of Evermore Creative Studio, the story of Evermore Park is ever-changing.

Each night that the park is open, actors play out parts of an ongoing story while guests (known in the Evermore Park fiction as “World Walkers”) can choose their level of participation. Many guests—whether groups of friends or families with children—come dressed in everyday street clothes with little information about the park’s ongoing story. Others, who may have spent time before their trip reading about the intricacies of that season’s ongoing narratives on fan websites and Facebook pages, attend in costume in a manner akin to a pop culture or comic convention . The park also has regular attendees who are experts that try to visit as often as possible. Major story beats are planned in advance, but the day-to-day lives of the characters and unfolding of the narrative is malleable because the actors improvise with one another and the World Walkers. With the exception of a novella published in 2020 to tide fans over until the park could re-open, Evermore Park has no media tie-ins—it is neither based on an existing franchise nor has been adapted into other forms of media. The only official method of participating is by living in or traveling to Utah and purchasing admission. This reveals the challenge of Evermore Park: it is a participatory experience unfamiliar to many Americans and, as a result, the park operators have had to adapt their structures by borrowing from other familiar forms of playful performance including (as elucidated in my travelogue below) immersive theater, live-action roleplaying, tabletop role-playing games, videogames, Renaissance Fairs, media tourism, and theme parks.

Close-Playing the Park in Two Visits

I had some sense of what to expect during my first trip to Evermore Park (which occurred during middle of the 2019 season of Lore), having heard it described as being like a “theme park without rides.” I also knew that other attendees might be in costume like any number of the geeky conventions or Renaissance fairs I had previously visited. Crucially, I knew it was participatory and prepared myself to engage as deeply as possible to take in all that it had to offer during the Saturday and Monday evenings of my visit. Assuming that most first-time visitors would go in with little-to-no knowledge of the on-going story, I purposely avoided learning any details not advertised on the website. Notably, Evermore Park does not publish an official record of events in the park nor the details of the story. Any visitor who wants these details must turn to the efforts of other fans who maintain the Facebook groups, a wiki, YouTube channels, and podcasts. Two-day ticket in-hand and liability and media release wavier signed, I boarded a plane to what would be the first of two field trips to study Evermore.

Evermore Park is located in a suburb of Salt Lake City called Pleasant Grove. Interstate 15—which leads south from Utah’s capital along the narrow band between Utah Lake and the Wasatch Range of the Rocky Mountains—is packed with suburban homes, shopping centers, and corporate offices overlooking the highway. Three-quarters of the way to Provo, Evermore Park is conspicuously tucked away amidst newly built business parks and fast-casual restaurants in a way reminiscent of Disneyland Resort butting up against neighboring homes in Anaheim, CA. The approach, via car, lacks the gravitas of a large sign announcing the visitor’s arrival and it has a simple parking lot adjacent to the entrance. Like Disneyland, Evermore Park is surrounded by tall fences, an earthen berm, and walls that keep the outside and inside worlds from mingling. By the time the park opened at 5 p.m. Saturday, a line of nearly one-hundred people had formed on the sidewalk outside the gate. The queue showed a mixture of costumed and un-costumed visitors. Most attendees came in groups and regular visitors greeted one another and the staff who was managing the line. A cursory estimate of the demographics revealed that the large majority of Evermore attendees were racially white, ages seemed to range from teenagers to 60-somethings, and there was a diversity of gender expressions represented in costuming.

The structure of Evermore Park demonstrates what it values in its visitors’ experiences. First, its offers an immersive and detailed place to explore. Second, its encourages visitors to become active participants in order to learn about the on-going narrative and the stories of the park’s many characters. Third, if a visitor’s intrinsic desire to learn about the stories is not enough, they motivate interaction through reward mechanisms like earning gold or ranking-up with the park’s various factions. In addition to its core mission of a participatory narrative experience, Evermore Park appeals to a broader audience through seasonal activities designed to draw in local Utahans. The ‘Lore’ season drew on the popularity of the Halloween “haunt” industry, wherein one might expect to encounter spooky corn mazes or haunted attractions populated with actors jumping out and frightening visitors. Thanks to the mix of attendees, the story beats of the weekend, and the seasonal event, this first visit turned out to provide a reasonable overview of the Evermore Park experience.

Unlike the uniformed/naïve approach I took to Lore, during my second trip in December—accompanied by fellow researcher Dr. Stephanie Williams-Turkowski—I took the opposite perspective and attempted to learn about the “Aurora” season’s on-going story ahead of the trip to see how the experience changed. I already possessed some knowledge of the characters from Lore (especially the Evermore residents) and was able to reference YouTube videos and a fan wiki site to identify new characters. This strategy enabled me to choose what level of familiarity I wished to perform and, crucially, made finding and referring to characters much easier. For example, I entered the Crooked Lantern Tavern and warmly addressed the owner “Suds” as an old acquaintance so that I could ask how he had been since the tumultuous events of Lore. When I met the Elves of Light, however, I feigned ignorance of their backstory that I had read online so that I could begin my participation with a clean slate. During this visit, Dr. Williams-Turkowski entered the park with only a bit of background knowledge, and we negotiated with each other on the fly whether I would step back in particular situations so she could have an unfiltered first-time experience. Dr. Williams-Turkowski also conducted semi-structured interviews with eighteen attendees while I attempted to follow along with the core events of the two evenings.

Trip 1: Lore, Fall 2020

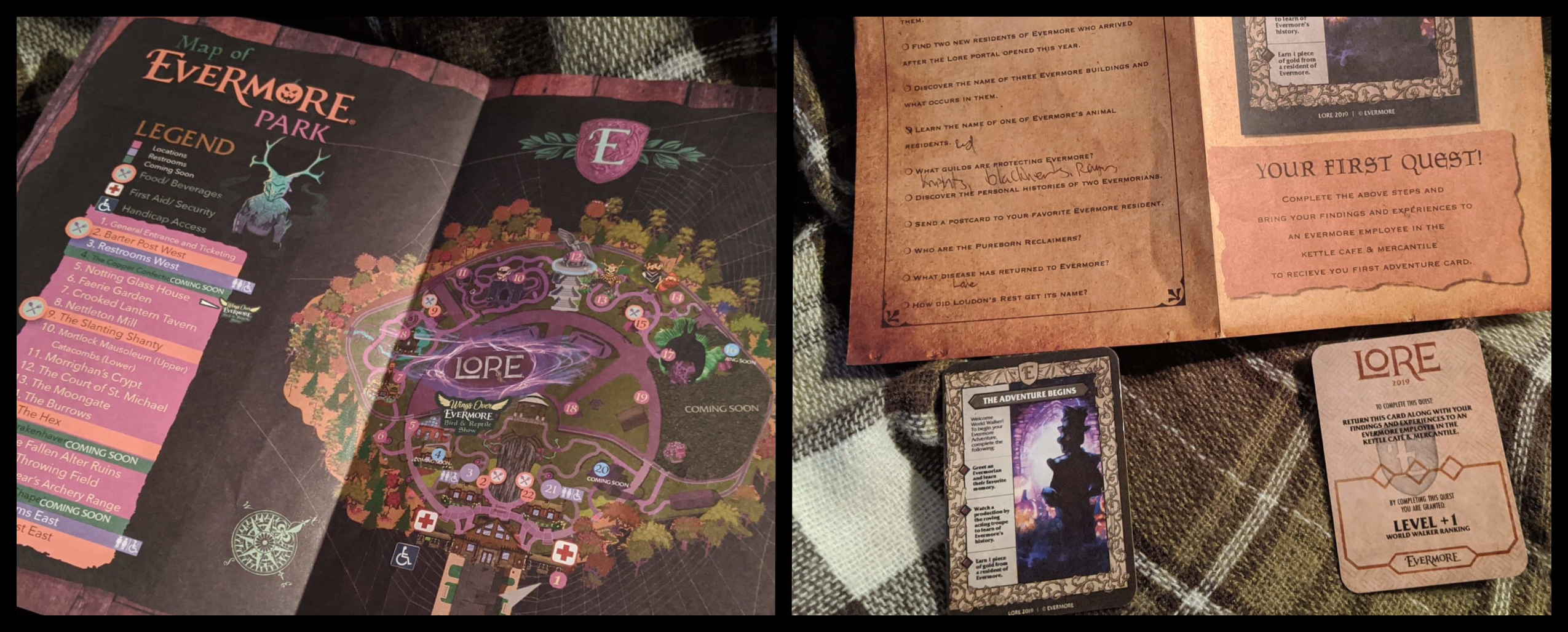

When I arrived at Evermore Park, I was given a guide that had a map on one side and a list of introductory quests on the reverse. The map revealed the village’s circular layout along an asphalt path. The entrance and town square greeted guests, who would then proceed past the gardens and glass greenhouse, the tavern, the crypt and mausoleum, a large courtyard and marble stairs in front of a colorfully illuminated statue of St. Michael, the Hobbit-like Burrows underground home, and the “ruins” that housed a fifteen-foot-tall talking demon. Though the circular path reconnected back to the town square, the eastern half of the park was still largely under construction at the time. In the center of the park was a hay maze, a handful of multipurpose tents and stalls, and an axe throwing and archery range. A series of quests—which were new as of the 2019 Lore season—were intended to orient a first-time visitor to the park. Some introductory quests offered gold as a reward which could then be used to buy information or influence (or a souvenir post card), while others led to new parts of the story.

The goal of these quests is to help World Walkers learn about the story of the park and Evermore’s residents, and to familiarize them with basic mechanics of participating: you can converse with the actors, the park is intended to be explored non-linearly, and Evermore is a persistent world that carries on in a clockwork fashion. Before entering, I was also given a copy of the Evermore Gazette—a broadsheet “newspaper” recounting some of the events that had taken place in previous weeks (though, without context for who the characters were, it was difficult to decipher its significance). The Gazette functioned like a television show’s “previously on…” segment and provided additional story “rabbit holes,” a term derived from Alice and Wonderland used to describe covert mechanisms in Alternate Reality Games that invite players to follow a thread without overtly revealing it as a game or quest (Montola et al., 2009, p. 27).

When the gates opened, I used the theme park tactic of heading straight toward the back of the town in hopes that I could skip past some of the crowd bottlenecks and encounter characters one-on-one. (In retrospect, this was a mistake because I should have tagged along with my fellow newbies to get better acquainted with the backstory.) Taking in the layout of the village, I was curious as to where actors would be stationed and what it would be like to approach them. I consulted the quests and asked a few Everfolk for information, though it became clear that characters who had more significance to the on-going narrative were less accessible than characters whose primary purpose was to answer introductory questions. Because attendees are permitted to wear costumes, one of the foremost important things to learn was that Evermore cast members could be identified by necklaces that display a glowing green gem. As the evening progressed, I got a sense of how the park was operating but had trouble following the main story thread. Upon my return visits, I realized there are not many mechanisms that enable new visitors to dive into the deep end this way. Evermore Park very much relies on visitors taking the initiative to ask questions of the actors, rather than the actors offering up invitations.

The 2019 Lore season’s story began when one of Evermore’s protectors became corrupted and transformed into the gruesome Fae King, who then aided creatures called the Darkbloods in infesting the village. Thus, not only was the overarching story of the Lore season appropriately macabre for Halloween, Evermore Park added additional “scare actors” to terrorize visitors in the catacombs and graveyard, turned the Burrows into a swampy cesspool using fog machines and green lasers, and built a hay maze for kids, Unlike the visitors who were ready to dive into the story when the gates opened at 5pm, local casual visitors looking for a Halloween haunt attraction arrived throughout the evening and eventually outnumbered the costumed visitors. The park was well-attended on Saturday until a light rain drove most away. Monday, owing at least in part to a favorable forecast, was much more crowded.

That weekend’s storyline presented a new challenge: the Darkbloods were beginning to infect Everfolk with a plague, slowly turning them into zombie-like beings with fading memories. It was a dramatic plot point that meant that a number of the actors were being taken out of commission for conversational interaction. Knowing that this was the primary conflict at the moment, I tried to get involved by asking various Everfolk if there was anything I could assist with. The idea came from my experiences with roleplaying videogames, and it seemed like an open-ended enough question. In a couple of instances, I was asked to deliver information to another character (“tell them I’ll meet them here at 9 o’clock”) or was instructed to ask another character for information. In the other instances, I was told by the character that they didn’t have anything for me to do and they suggested I ask somebody else. Both of these cases presented the same problem, though: as a newcomer to Evermore I didn’t know who most of the Everfolk were. And asking around to identify who they were was made more difficult by the fact that character names, while unique, were hard to remember and easy to mix-up: the Elven archer Vaella, Ariadne the Princess of Spiders, Kyrah and Caderyn and Kilyrie, Arawn the Knight Captain and Oran the Pirate. Frustrated by my inability to accomplish the goals I had set out for myself, I turned back to a pre-existing structures of participation: the guilds.

Evermore is home to a number of guilds that group particular characters into factions. During Lore 2019, there were the Knights of Mythos, the Elven Rangers, the Bards (comprised of the Acting Troupe characters), the Blackhearts, and the Pirates of the Last Shackle. The tenants of each guild are multi-purpose: they influence that guild’s motivations and involvement in the day-to-day of Evermore, they function like a “personality quiz” that can align a visitor’s allegiances to invest them in particular characters, and they are a utilitarian narrative justification for the tutorial tasks the guild assigns that help orient visitors to the dynamics of the park. As I learned, joining a guild is a matter of completing a series of three tasks that represent the ethos of that group—the structural behind-the-scenes purpose of which is to promote exploration and interactivity. For example, the Knights Guild represents honor, loyalty, and wit while the Blackheart Hunters value bravery, strength, and wisdom. The tasks often involve seeking out other characters to talk with and learn something from, visiting a specific location, performing for other characters in the park, answering riddles and reciting stories. The actors in the park, so long as they are not presently involved with either another World Walker or story event, are prepared to make suggestions that will help visitors fulfill the requirements of the various guilds. I wanted to join the Pirates of the Last Shackle, which involved me showing the value of freedom by asking someone to take my photo while “meditating on being incarcerated” in a dangling cage, testing my luck by trekking through the scare-actor infested crypt, and proving my boldness performing a dance for one of the members of the Acting Troupe. When all three were completed, I returned to Captain Duphrane who taught me the sign of the pirates (a hand gesture that could be used to indicate my membership to other actors who wouldn’t know me) and gave me additional “insider” tasks that I could complete while waiting for the induction ceremony near the end of the night. Again, I found myself frustrated by not knowing the names of characters while trying to accomplish these new tasks. With the cold rain coming down steadily and the induction ceremony still a ways off, I left the park discouraged.

The second night, in many ways, was what the first should have been. The four hours of experience I had from the previous visit were an immediate boon. I could greet the handful of characters I knew with a knowing nod and friendly hello. As opposed to Evermore’s regular visitors, who the actors come to know, new visitor like me need to indicate to an actor that they should know me within the fiction. Gestures like this function as an immediate shortcut that changes the dynamic between World Walker and Everfolk. During this second evening I was successfully able to join the Pirates Guild, followed the core story of the infection more closely, and felt more confident in my interactions with both the Everfolk and other visitors. I closed out the second night wrapped up in the action: Hal, one of the infected members of the Rangers Guild, had been banished to the quarantine zone surrounding the Statue of St. Michael. We learned that Hal was working on a cure for the infection and needed to smuggle ingredients to his laboratory to work on his concoction. The quarantine area was located at the back of the park whereas the lab was at the front. Thus, a group of World Walkers needed to band together to sneak him away. In this scenario, Hal was permitted to walk the grounds of the cemetery adjacent to the quarantine zone. So when the clock struck 9:30 he began pacing a route through the cemetery and the mausoleum. We followed to provide protection and, when another Everfolk spotted him attempting to deviate, he resumed walking the same path again. The behavior was like watching a videogame character on a programmed patrol route. Another World Walker (who I later learned is a regular attendee) played the role of antagonist to us and tried to foil our escape. I then devised a plan and whispered it to my companions: when we reached the mausoleum, our group would flank the entrances to block the pursuing World Walker while Hal was inside. I quickly threw my rain jacket over top of him and pulled the hood up to hide his long blonde hair. I then put on my other coat and pulled its hood up and we split the group into two different directions. I resumed walking Hal’s route and our adversary lost track of the real Hal in the mix-up. (I then had to break the immersion in order to find someone from the other group to retrieve my jacket, at which point the park began closing for the night.) It was only in this final hour of my trip that I understood what fans have come to love about Evermore Park.

Trip 2: Aurora, Winter 2020

As previously noted, I prepared heavily for my return trip during the winter season. I listened to summary podcasts of what had happened since my Lore visit. The Portal to Aurora brought with it the cheery Elves of Light who were being chased by the steely-eyed Wolves of Winter. Ahead of the trip, I made note of the new characters in my phone’s notes app by copying their names and headshots from the Evermore Fans wiki. (This was used to keep track of who I met rather than to approach the characters as if I already knew them.) I was congenial toward the characters I met on my previous excursion, such as Suds the tavern owner, Sir Philip the postman, and the singing dwarves Lanny and Turno. I shed my affiliation with the Pirates and decided to try joining other guilds to meet new characters. Another important event that came into play during this visit was an unexpected run in with the woman who runs the Evermore Fans Facebook and YouTube pages. Recognizing her (and remembering seeing her husband during Lore), I introduced myself. I learned that she and her family visit every night the park is open and are responsible for nearly all of the Evermore footage that can be found online. Their deep understanding of the narrative and familiarity with all of the characters around Evermore means that, like intrepid journalists, they can chase the story. The family participates together, recording videos from multiple angles or splitting up when necessary to capture events happening simultaneously in different locations. Not only were the videos themselves useful as primers before visiting, but I could be assured that if any member of the family was rushing off with camera in hand, I should pursue them because an important narrative event was bound to be taking place.

During the weekend of the Aurora visit, the central conflict was that the Elves of Light had been providing the townsfolk—who were slowly starving because the events of Lore destroyed their crops and cut off their food supply lines—with a “snowberry pie” that instantly satiated those who ate it, but inflicted them with a form of manic joy that seemed to be controlling their minds and bodies. The newly “pie-eyed” Everfolk were rambunctious and humorous; this gave the normally serious actors a chance to joke around and behave like children on the playground at recess. The Wolves of Winter, distrustful of the Elves, attempted to convince Everfolk not to eat the narcotic snowberry pie and the evening featured a number of confrontations between characters. I was also privy to an intimate gathering inside of Mausoleum on the second night, when the Wolves of Winter broke one of the Everfolk free from the Elves’ spell and recruited her into their pack.

On the first night, we encountered an example of a repeatable story-relevant task that could be assigned to World Walkers. The mystic wizard Zhodi—who had expended much of his power in a previous weekend while trying to save another character—had taken up meditation in the catacombs. World Walkers who stumbled upon him sitting in a corner would notice that he was infatuated with the twinkling lights being projected on the stone walls around him. If they chose to ask him what he was doing, Zhodi would respond by wistfully ruminating about wanting to make “the spirits happy” (Evermore Fans, 2019). If a World Walker decided to pursue this further by asking how they could help (which we did), Zhodi suggested it might be possible to feed snowberry pie to the spirits and that he would like to know the ingredients. Later, on subsequent trips through the catacombs, we overheard him make this same request of other groups. In this way, this particular challenge could be “instanced” — a term from online games in which individuals or small groups of players receive the same quest as one another but complete that task as if it is unique to them.

In the same way that Lore was designed to complement the Halloween season, Aurora featured Christmas trappings. A children’s choir performed carols, the Elves of Light dressed in red and green outfits trimmed with white fur, and the festively lit gardens and often snow-covered grounds were ready-made for Instagram. Evermore Park, in this way, could serve as holiday leisure for people not invested in the narratives of the park. Anecdotally, we spoke with a number of people (including a number of parents attending with their children) who explained that this was the reason they were in the park, though none of these were captured in our interviews.

How Visitors Make Sense of Evermore

“It’s difficult to explain because Evermore is so unique. Because it’s like a play. It’s like a theme park. It’s like a “Choose Your Own Adventure.”

Evermore Park strives to be the kind of place that would be described as “a well-designed environment, [in which] agency and immersion reinforce one another through the active creation of belief” (Murray, 2011, p. 24) and the two prominent high-level concepts that emerged when interviewing participants were the way they expressed the values of immersion and interactivity. On the surface these may seem obvious, but the interviews reveal how these ideas are informed by frames of reference from other media and how that drives different level of participation. Following Biggin’s analytical approach to interpreting the language that Sleep No More fans had used to describe the performance, we examined Evermore visitors’ discussions to gain insight into how they make sense of the park. Based on our interviews, the most frequent media descriptors were “theme park” and “live-action Dungeons and Dragons.” These were complemented with mentions of other tabletop RPGs, board games, videogames, World of Warcraft, and Lord of the Rings, and amusement parks and theater. Emerging from these examples were the intertwined qualities of immersion and interactivity.

Valuing Immersion

Our interviewees (whether organically or as part of a prompt) agreed that “theme park” at least in-part applies to how they would characterize Evermore Park, but it always came with an elaboration that alluded to an imagined definition of what a theme park is and is not. “I heard it described as, like, it’s a theme park but there's no rides” (Michelle, personal interview). “I say it’s an interactive amusement park; like an immersive amusement park” (Finley, personal interview). “Theme park” was repeatedly as shorthand for a narratively themed experience like one would find in places like Disneyland or the Wizarding World of Harry Potter. This aligns with early theme park scholar Margaret J. King’s interpretation of theme parks as “total-sensory-engaging environmental art form built to express a coherent but multi-layered message” (King, 2002, p. 3). Drawn from a pre-history that includes landscaped gardens, lavish palatial architecture, fairs and exhibitions, King’s description of the theme park could be applied to Evermore Park. But it does not recognize the tight association between theme parks and rides in the popular consciousness. During a promotional campaign when Evermore Park was first announced in 2014, CEO Ken Bretschneider told Theme Park University that he viewed the park as “location-based entertainment” and wanted to focus on storytelling because, “We have polled people and found that when it comes to a Disney experience, guests tend to rate attractions like Pirates of The Caribbean or Haunted Mansion higher than the thrill attractions” (Young, 2014). Rather than experience the pirate town of Tortuga from a boat in a canal track, Evermore’s creators wanted to give visitors the freedom to wander around the sets. In the lead up to the park’s opening in 2018, Chief Creative Officer Josh Shipley explained on the ThrillGeek podcast that “Evermore is a giant theatrical stage […] We have to correct people when they ask about Evermore and refer to it as a theme park because a lot of times you heard the word ‘theme park’ and you think of the D[isney] and U[niversal] out there and you tend to paint these different pictures with attractions and stuff, and we are very much an immersive theatrical space. […] a space that you walk into to react and be a part of” (ThrillGeek 2018). Walking into a park fully surrounded by walls and a berm has a positive effect on the “magic circle” quality of the space: “It's a weird because, you know, we are staying at the hotel across the way and then you come in here and then it's completely… it's a different realm, right?” (Michelle, personal interview).

Why visitors tend describe it as a theme park, then, can be attributed to resemblance: The ‘theming’ of a theme park is what “renders this strangeness domesticated,” describes theme park scholar Deborah Philips. “It is the employment of well-loved and recognized tales that makes the ‘empty space’ and alien territory of the theme park pleasurable and familiar” (Philips, 1999, p. 91). Absent of rides, elements of theme parks present in Evermore Park include: the fabrication of other places through architecture, navigable physical space, the use of environmental storytelling, narrative attractions (in Evermore’s case, tableau performances), and design informed by the convergence of many media (Baker, 2019). Mia, who described it as “Disneyland for nerds,” elaborated that Evermore Park’s attractions are designed to be enjoyed by geek culture fandom in the same way Disney parks appeal to fans of Disney animation or Pixar (Mia, personal interview).

In the realms of entertainment, media and theater, immersion and illusion carry particular (and perhaps contentious) meanings. Media historian Janet H. Murray describes immersion as an illusion in which “a stirring narrative in any medium can be experienced as a virtual reality because our brains are programmed to tune into stories with an intensity that can obliterate the world around us” (Murray, 1997, p. 98). But, as Lizzie Stark (2012) describes, even though the desire to play make-believe appeals to a broad portion of the population, not everybody is going to feel comfortable playing Dungeons & Dragons or cosplaying at their local comic convention, and therefore need guidance when joining LARP experiences. In Evermore, parkgoers need not plunge into the deep-end of the immersion pool–they can wade in and out as the evening requires. This is a fascinating tension. Striving for immersion, Evermore Park faces an uphill battle. Its visitors come to it with different levels of experience with related forms of media, so it cannot fully rely on familiarity with any single reference point. Immersion can be broken if the actors have trouble improvising in a given scenario, if a piece of the set (like a Styrofoam jack-o-lantern) blows away in the wind, if the visitor runs into a narrative dead-end or becomes frustrated by their inability to engage.

However, in our interviews, the use of “immersion” by parkgoers was not an indication of “obliterating” the real world but rather seeking out exciting potential. “Immersion” (or “immersive”) was used by our interviewees in a handful of ways: requiring participation, engaging in a way other media are not, and separated from daily life. In contrast to other themed environments that may be visually/physically immersive, immersion in Evermore Park is often collated with agency: “I like the immersive part about it and just being in the world and then as an actor being able to participate and have fun like this is my sort of play” (Finley, personal interview). Perhaps counter-intuitively, watching other people become immersed is its own form of pleasure. William, who described having visited “many times,” said, “I see the same people. Not just the actors. People get really immersed.” But he surprised us by admitting that immersion isn’t necessary for enjoyment: “We just walk around. I never do any of that” (William, personal interview). (William proceeded to contrast Evermore Park with the Renaissance Fairs he attends, which he felt were not immersive.)

Visiting Evermore Park may not be the typical form of “fan pilgrimage” (Couldry 2005; Brooker 2007), but it has earned a reputation as a place where visitors can bring their creativity to life. Costuming was perhaps the most commonly referenced mechanism for immersing oneself among our interviewees. (Author’s note: we did not dress up during either visit to the park and thus did not have first-hand experience with this aspect.) As Marco explained, he and his partner dressed in costume because, “we like to be fully immersed—that way we leave our own portal [“the real world”] behind.” Interviewee Finley elaborated on this further:

“[Dressing in costume] has an impact on how I'm playing in this world too. Like, I walked in and the actor came up to me with an accent and I was like ‘okay, we're going in with an accent!’ just to fit in and just to feelin it more. It's just easy to slip into it.”

The subtext in our conversations with both new and veteran World Walkers was that immersion was less of an overarching goal than an invitation to participate. Whereas cosplay at a pop culture convention relies heavily on representing characters from media, Evermore Park’s attendees dress more like visitors to a Renaissance festival—genre fiction and period costumes using “generic representation” (Hale 2014). Some visitors enjoy costuming for costuming’s sake, while others transcend the “generic representation” description by bringing an “original character” (OC) developed outside of the park into Evermore’s world. Theme Park ASMR’s Beedy, who had been looking forward to their first Evermore trip after learning about it and following along online, said in their write-up:

“I attended with my dnd party and so of course we made up our own characters. I came as ‘Sundew the Bog Witch’ (hence me joining the coven) and my costume helped me garner characters’ interest and was a great conversation starter” (Beedy, 2019).

Shari concurred:

“We played Dungeons and Dragons. So, I like to dress up. I like to make clothes. And this is, if like I was thinking of it kind of like an extension of when we dress up for the Ren. Faire at home […] maybe like a little lower-key Comic Con. But it adds to the experience” (Shari, personal interview).

Michelle reported,

“I thought about coming here in street clothes and just being […] No, like, I feel like it's kind of an excuse to dress up—put on elf ears. No one’s going to look at me too weird” (Michelle, personal interview).

And Mia mused that dressing up is important because,

“that's part of like what the magic of it is, isn't it? [It’s] that you walk into this fantasy experience and it’s all the TV shows and the books you've read, and then you're in it, so [you are] of course wanting to be your own character.”

When contrasted to other similar media, Alan explained that even though roleplaying games are “mentally encompassing,” when compared to Evermore they are “not as immersive as […] dressing (in costume) and everything like that” (Alan, personal interview). And, unlike the rigidity of videogames, “the really cool thing about here is […] because they've got the actors and they're improv-ing, they can gently steer you back without it feeling like a big clunk, or they can kind of take what you're saying and send you off in a particular different direction” (Rhett, personal interview). The “clunk” that Rhett describes is the place where a text breaks immersion by revealing its illusion.

Valuing Interactivity

“Interactivity” was seen in contrast to being a passive audience member, demanding effort from the visitor like a videogame or tabletop roleplaying game. “Interactive” was also often used as a qualifier to establish variation from the norm such as an “interactive theme park” or “Renaissance Fair with live-action roleplaying.” Comparisons to Dungeons & Dragons are frequent because it is the singular piece of media regularly lauded for its spontaneity, malleability, and socialization. And two interviewees referred to Evermore as similar to the popular HBO show (based on the 1973 movie) Westworld. One of the interviewees even clarified that it was like a “PG Westworld,” to reference its family-friendly atmosphere. Westworld’s promise of a dynamic, interactive experience is brought to life not by robots, but by Salt Lake City’s pop culture fans and theater community. Returning to Dixon’s categories of interactivity, our interviewees spoke about participation, conversation, and collaboration.

In a perfectly illustrative example of spontaneity and interaction, Aubrey (a frequent World Walker) began to describe the way visitors are “actually here and you can see these people, you actually interact with [the characters]” when suddenly an Everfolk named Vaeilla (who was behaving like a child with a sugar high) tried to interrupt the conversation. Aubrey tried to proceed: “You can actually intera—you can actual—whatever you're, you're tryi—,” he stumbled before turning to Vaella to implore, “I’m in an interview, please be nice!” Aubrey’s companion leaned into the moment and told Vaella “Go play hide-and-seek, I’ll come find you in about ten minutes!” Aubrey was able to continue, “So you're not just interacting with the characters, you’re crying with them, you're rejoicing with them, you're playing with them, you're fighting alongside them. So, it’s way more powerful and way more interactive.”

Interactivity, of course, is a two-way street and often how much a person puts in is how much they get out. Laura, an interactive theater performer from Las Vegas herself, explained that though she frequents the Renaissance Fair in costume, Evermore allows her to evolve her own relationship to the park: “Every time I leave, there was something in my head like ‘oh I can change this, I can do this.’ This is something new I've learned from the character—a lot of it teaches like, life lessons” (Laura, personal interview). Rhett, who had attended previous seasons without fully engaging, explained that “I decided to go full in, as you can tell, and say okay let’s go and see what the stories like how far that can go I am interested in how they construct the place how the actors interact” (Rhett, personal interview).

Interactivity meant not only being able to converse with the actors, but also a sense of narrative agency. Unlike most places the average person encounters actors, Evermore is surprising in that “you can actually interact and effect the story” (Gem, personal interview). For the fans of Evermore Park that we interviewed, the impression that they could impact the story was a significant part of the magic. Though none of our interviewees believed they could totally dictate the narrative outcome, they did think it was possible to nudge events. Interviewee Finley recognized how structure of interaction allows for

“specific events where you know, if I tell another character, this is happening, they can come in and stop it […] So it's not like, ‘ Oh, this is scripted,’ there are so many different endings you could have to these stories. It’s very exciting to know a lot of World Walkers affected what happened during the [Lore 2019] war. So, this is really cool how you can impact the story yourself” (Finley, personal interview).

Mia concurred, saying,

“I think World Walkers do a ton to, you know, drive the story forward and really make it what it is. And [World Walkers] who portray characters really do that, too. I believe when they World Walk and stuff, but no I think World Walkers really do have a huge effect” (Mia, personal interview).

Anecdotally, the regular visitors who came dressed up believed in their agency because they had experienced it or witnessed it in the community. Less frequent attendees did not answer with the same enthusiasm. Tanya’s response to the question if World Walkers impacted the story was more hesitant: “I think we do. [By way of] the people we interact with.” Her partner Alan conjectured that it was more likely the way “[we] create our own story.”

Jamie expressed a similar sentiment:

“I don't know. Okay. Yes, kind of, we were here months ago and we were here for two nights [and] like the actors remember. Yeah, some of them […] remember your name. So, I mean, at least for like our little bubble that we created. Yeah, like we have carved our little characters’ miniature niche in the story.”

Rhett responded,

“I don't know, I've heard that in the original Lore people that were ‘playing the game’ did manage to influence what was going on, for example the relationship between Suds and Clara. There's kind of been a running thread through the story that actually came from a participant rather than the scripting team. So that was kind of fascinating. But I have no idea.”

What seems most likely is that the more experienced World Walkers have evidence of impacting the story and thus have come to value it, while less frequent visitors have heard (through promotional material or discussions online or TripAdvisor reviews) that it is possible, but it’s not a thing they would know how to approach or would even feel motivated to do. The conflict at any given moment is easy to follow—something bad is happening or somebody wants something—but Evermore Park’s nightly stories and arcing narratives are convoluted. Helping a guild leader or the Mayor is quite different from understanding the kinds of character motivations and mythology that guide the park’s story bible. For visitors, there’s an air of mystery around the operation of the park. Who writes the stories? How involved are the actors and how much is determined by the behind-the-scenes staff? How do they keep track of what happens on a given night? Rhett, who attends frequently, pondered this question:

“I'd love to get us behind the scenes here. To see if they have like a big board with people. I mean do they… I've had actors come up to me saying my name, who I haven't told my name to. So, the question is, am I on the board back there with ‘this is him’? I don't know” (Rhett, personal interview).

Evermore Park’s welcoming attitude toward costuming returned as a theme in promoting interactivity. As Jaime said,

“I mean, for just general cosplaying we go to the Renaissance Fair in our town. This is the first time I would say I've done anything that could probably be constituted as LARP. It’s not really LARP. I don't have like a whole sword or anything… but we made our characters and we're here doing our little adventures and stuff” (Jaime, personal interview).

Laura described how costumes function as an “interface” (Lancaster 2001; Godwin 2017) between her and the characters in the park: “I feel like you're able to immerse and talk to the characters better if you're in an outfit. Because if I'm in my normal like human clothes, I'm just not in the headspace of Evermore.” Rhett concurred: “the thing that’s brilliant about it—the way they've structured it, you know—you come in in normal street clothes and the actors have to judge what level of engagement you're going to do.” Michelle also confirmed the value of the role-playing experience while using Evermore Park as a platform to develop her O.C. (an “original character” created to participate in a storyworld) by explaining how she was “trying to think about […] getting in this headspace. How would [my “original character”] Meena react to this?” She then proceeded to contrast her group’s usual dynamic ( “usually [he] is the DM, so most of the time like when I played D&D, […] we're on opposite sides of that [dungeon master] screen) to the collaborative quality of sharing Evermore in which “we're actually able to do this together.”

Samuel discussed the way that dressing in costume extends beyond interactions with the actors of Evermore Park and into interactions with other visitors:

“it seems like the people in the park seem to want to approach people—if you're more comfortable approaching other people—that are also here [in costume], because they know that you're here to be in character. You're here to represent something. So, I know I'm going to be able to get the RP [role-playing] experience that you want, I know I can deliver what you're looking for. Because I know what you're here for: you're here to play here.”

Samuel went on to create a dichotomy between costumed attendees looking to role-play and become a part of the story, as opposed to “World Walkers” who are just tourists:

“Whereas if you're in street clothes, you're here as an observer (the world Walker thing). You're here as the observer. You're here maybe with your family and you have kids […] But yeah, I think the dressing-up experience just kind of enhances it. (Costuming at Evermore is wonderfully complex and deserves further study.)

In addition to social interactions, interactivity through game-like mechanisms helps orient and structure the visitor experience. Many of our interviewees described the park as being like a living tabletop role-playing game (more so than just a traditional LARP), while others spoke of it like single-player videogames and MMORPGs which should be familiar to “somebody who's played World of Warcraft or Everquest. Final Fantasy” (Marco, personal interview). Given its influences and content, it’s easy to see why someone might describe it as a “video game" theme park (Victor F, Trip Advisor). The game systems have changed between seasons but have included quests, elements resource management and trading, information gathering and puzzle solving, and generalized tasks (akin to “fetch quests”). The videogame-like ideals were part of the park’s mission before opening. As former Chief Creative Officer Josh Shipley explained in an interview with the amusement and entertainment trade publication Blooloop, “If you want to enjoy it passively, that’s fine. But if you are an Evermore Park player/hard-core fan, and you quest multiple times, you actually begin levelling up. Just as you would in an online game. Your established personality and character will level up; the park will actually start to recognise you, based on your seniority” (Merlin, 2018). These plans—which would have relied on digital technology—were likely shelved during the early years of the park because of their expense and because the physicality and human-nature of the park were so appealing. (We conjecture that this is the reason the park has come to appeal to fans of immersive theater, role-playing, and tabletop games.)

During Mythos 2019, Evermore sold five sets of “Adventure Cards” as way of structuring participation in the park. Visitors completing the Apprentice rank introductory tasks could then ask to buy the first set of Mentor rank cards followed by Elite, Paladin, Master, and Champion. Quests on the cards served primarily as a checklist of activities available in the park. One card specifically tasked World Walkers with visiting the archery range and gaining the approval of the training master. Another card gave the more generalized quest of earning five pieces of gold and donating it to the guild of their choosing. The Adventure Cards used during Mythos were a double-edged sword: though they provided a convenient structure, they minimized spontaneity and discovery. YouTube personality Ginny Vi described this experience in her video recap: “During the first hour-ish (when we completed this first level) it def[initely] did feel like everywhere we went there were a dozen people already there doing the same thing as us. Which is a little unfortunate, but this first quest does sort of function as a tutorial level on how to navigate Evermore and interact with the characters. Once we got past it, things got a lot more interesting and a lot more unique to our party” (Ginny Vi, YouTube). These cards were retired after one season. Though difficult to manage, the quest-giving works well when it comes directly from the Everfolk. The actor who played Faldo, responding to the YouTube video posted by Ginny Vi, mentioned that “Our cast is full of actors passionate about character building, and oftentimes half of them are DMs (dungeon masters).”

The example of “instancing” quests that we encountered during Aurora (in which the Evermorian Zhodi was asking World Walkers to learn what magic was contained within the Snowberry Pie) was echoed inside the cozy, spiritous Burrows home. Listening closely, we could hear the “Elves of Light” and their caretaker Gafruk throughout the evening giving out pieces of this recipe to inquiring World Walkers. Successfully returning to Zhodi with the information earned some participants gold, though by the time we returned he only had a small plastic trinket he had received from another World Walker. Again, as is prevalent in online games, emergent systems like these artifacts—plastic gems, charms, cards, etc.—developed into an unofficial economy in the park by fans who wanted a way to trade with the characters and each other (Thelin, 2019). Similarly, as gold became more common (introduced into the park both through official channels and unofficially by visitors buying fool’s gold at hobby shops), the park responded by developing an economy. By the end of Aurora 2019, regular visitors could store the park’s official gold currency in a bank. Gold was subsequently used to purchase the rights to buildings around the park.

What the performers really desire, it seems, is for structured tasks to arise naturally out of the conversations between World Walkers and the Everfolk. When the hosts of the World Talkers podcast interviewed park actor Bobby Cody, he explained

“But the real 'meal' is talking to us, engaging us, and asking us more than just, ‘Do you have gold for me?’ Which became a huge annoyance for a lot of us because people would just come up and not even … no social interaction other than, ‘Hey, I want gold. Hey, give me silver.’ And so we would be like, ‘Are you robbing me?’ I would spin it all kinds of ways, but some actors got very frustrated by that. And even some actors got frustrated when people were like, ‘Hey, you have a quest?’ But we are kind of in a video game, so …”

The familiarity of quests and treasure hunts will only get newcomers so far in Evermore, so the only way for regular visitors and fans to advance through the story detail is to become involved personally with the Everfolk. Biggin’s work well articulates the scholarship regarding the spectrum of levels of involvement in fan practices, highlighting in particular Susannah Clapp’s observation about “aficionados” of The Drowned Man who “poke eagerly into a place, suss out whether there is any action and move on” (Clapp, cited in Biggin, 2017, p. 99). These aficionados purport to have expert knowledge and are akin to the ‘hardcore’ players of videogames who spend their time probing a game’s inner workings, or a theme park superfan who is quick to share optimized trip plans or the detailed history of a ride. During my visit to Lore 2019, I was watching one of the Everfolk who was slowly being overcome by the plague and a crowd of visitors had gathered to watch the tableau. But I was distracted by a lone World Walker who was holding a book, asking one of the members of the Acting Troupe about one of the passages inside. What I could suss out was that the book may contain some secret or important information, but I could not understand why this man was entrusted with a prop or why he was having a personal moment with a single actor. It was not until I returned for Aurora 2020 and saw this same man again that I realized he was one of the World Walkers who attended every night and was deep down the rabbit hole. The Evermore fan community—many of whom cannot travel to the park more than once a season—shares information and theories online to probe the depths of the story. But they also (through orientation blog posts and responses to newcomer questions of Facebook and Reddit) tend to agree with Biggin’s assertation that though aficionados can reveal insight into the media, they are neutral on whether there is “intrinsically a ‘right’ or ‘better’ way to engage” (Biggin, 2017, p. 99). The “real” way to enjoy Evermore Park is to learn the rhythms of its storytelling, the motivations of its characters, and the mythology that guides its infrastructure. But the actual way is by constantly moving back and forth along the Dixon’s spectrum of immersion while drawing comparisons to other familiar forms.

The Future of Evermore Park

In some ways, Evermore Park is reminiscent of media tourism destinations such as The Lord of the Ring’s Hobbiton site in New Zealand, the Making of Harry Potter at the Warner Bros. Studio Tour London, and the recently opened Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge at Disneyland in California and Hollywood Studios in Florida. Like Disneyland, it is a travel destination that is described as an inimitable experience worth venturing to. It is a highly themed theatrical set adorned with a level of detail that one might find on TV or on a movie screen. Its stories are familiar—drawing from character types and mythology that have pervaded fantasy media. With the exception of a self-published novella intended to bridge seasons, Evermore Park has no referent in film, television, literature, or games. Evermore Park is the media.

When it was announced that the park was re-opening following the COVD-19 pandemic that forced amusement venues across the United States and the globe to shutter for months, it was immediately evident that changes to the structure were coming. The time away from the weekly grind of directing, fabricating and performing provided time to reconsider how the park could financially continue to operate. Evermore Park had been experimenting with new streams of revenue such as corporate events and private parties before its closure. And, when it re-opened for Pyrra 2020, it looked like it was trying to solve the issue at the very core of this discussion: how can you introduce a broad audience to immersive and interactive play? The answer was “Epics”—a new repeatable quest structure in which participants can sign up for timeslots to embark on a single, nightly adventure. This replaced the real-time theatrical performance tableaus that had previously told the town’s stories (but were easy to miss). These short “campaigns” (in tabletop RPG parlance) were easier to manage, required fewer actors, and helped congregate the audience in a more structured way by providing predictable performances and guided navigation. They also required an additional fee but could be “replayed” to gain new information or affect their outcome differently. During the summer of 2020, the “base price” Evermore park ticket still included interactions with characters, but the plot was relegated to a paid experience. In 2021, the future of the park’s operation is uncertain. Much like the fictional portals inside the park that open up to new fantastic worlds each season, there has long been a sense among Evermore’s fans that it could suddenly close its gates and the magical experiment will be over. Based on a retracted Facebook press release, rumors have circulated that the park will do away with its serialized narrative performances and instead become more like a themed pleasure garden with nightly entertainment. If so, it will lose what made it a special place for so many people. Its legacy, however, will be the grand experiment its founders, hardworking employees, and ardent supporters undertook to build a living participatory storyworld. In the same way it borrowed from related forms of media, Evermore Park will surely influence future designs of interactive entertainment.